| Andrew Booth and the Forgotten Computers |

| Written by Historian | ||||

Page 1 of 3 When you think of early pioneering computers you tend to imagine huge monsters with thousands of valves and a team of technicians to match. Small computers started earlier than you might think, as the remarkable story of ARC, an early British computer proves. It was the brainchild of Andrew Booth, also known for Booth's Multiplier, a technique that is still used in today's smartphones. In the late 1940s, four groups in the UK were looking at building digital computers. The best known were at Manchester University which can lay claim to having the “first working stored program computer” thanks to the efforts of Freddie Williams and Tom Kilburn and at Cambridge where a team led by Maurice Wilkes built EDSAC, the first machine to have users. A third group at the National Physical Laboratory built the ACE, designed by Alan Turing. This article is about the final and least well-known British endeavor. It was undertaken by Andrew Booth at Birkbeck College, London University which concentrated on building smaller machines. Booth had the radical ambition for that time of building a computer that was cheap enough that each university could own one. This was at a time when the NPL ACE was being talked of (at least at NPL) as sufficient for the whole of the UK’s needs!

Andrew Donald Booth

Andrew Booth's father was an entrepreneurial engineer who came from a long line of engineers but seemed to interpret engineering in the broadest possible sense. Andrew helped his father with a range of different projects - a solid state battery charger, an automatic ignition advance and an anti-mist mixture for mirrors. He was sent to prep school and learned nothing very useful for an engineer - Latin, Greek, French and so on. When he received a score of 6% in a maths exam his father decided that it was time to do something about it and started to teach him maths. When he re-sat the exam three months later he got 100%. By the age of 10 he had mastered differential and integral calculus and was sent to public school. At public school he wasn't happy and didn't fit in because he lacked an interest in rugby but he did enjoy the maths and physics lessons and eventually moved on to Cambridge to read mathematics. Unfortunately he didn't enjoy Cambridge maths and spent his time listening to physics lectures and, after a talking to by his tutor, he left. This annoyed his father so much that he entered for the next University of London External Degree examination and got a first. After this success he did a variety of jobs including working in an insurance company, a motor engine factory and an aircraft factory. He decided to return to university to study X-ray crystallography, at Birmingham, which was a relatively new and exciting subject at the time. It was also a subject that suffered greatly from not being able to work things out quickly enough. The team he worked with was heavily involved in computational work which, following Babbage, he found no fit work for a gentleman. As a result his mind turned towards the production of a computing device to speed things up. While a graduate student (1944) he produced three small analog computers that helped specifically with crystallographic calculations. Automatic Relay ComputerHis scholarship at Birmingham was provided by the British Rubber Producers Association and its director, John Wilson, became his life long friend and supporter. While working at their research laboratories at Welwyn Garden City he started on a design for the ARC, the Automatic Relay Computer. This was no general purpose computer. It was specifically designed to do Fourier synthesis, an essential step in determining a crystal’s structure. The machine used paper tape and a ROM built using selenium diodes. At this time he was unaware of the work going on in the USA into electronic computing. In 1946 he was appointed as a lecturer in theoretical physics at Birkbeck College in London. The head of his research team was Prof. Bernal, a man that many think should have got the Nobel Prize along with Crick and Watson for the structure of DNA. Bernal was as interested in computing as Booth and he had heard about the work going on in the USA. In 1946 he arranged for Booth to go and see just what was happening. On this trip Booth met Warren Weaver, Jay Forrester, Vanavar Bush, Howard Aiken and John Von Neumann - all leading lights in US computer development. Warren Weaver suggested that Booth pay a return visit in 1947 as a Rockefeller Fellow at an institution of his choice. He chose Princeton and Von Neumann.

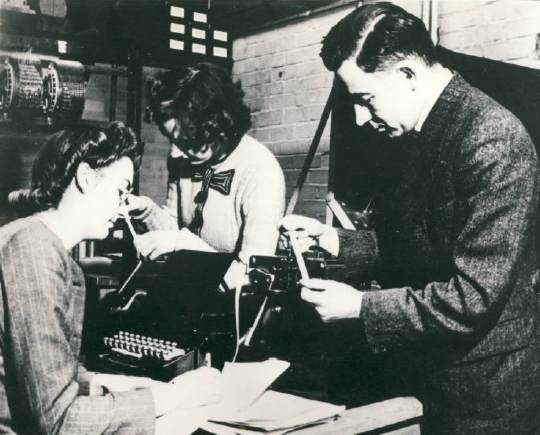

Kathleen Britten, Xenia Sweeting and Andrew Booth Back in the UK he continued to work on the ARC and enlisted the help of two "young lady assistants". One of them, Kathleen Britten, was to be come Mrs Booth, and then Dr Booth, a few years later. The two assistants were responsible for building the machine and not programming it as you might expect. When Booth left for the US in 1947 Miss Britten was sent along to help and they travelled together as first class passengers on the Queen Elizabeth. When they arrived they found that actually very little was going on by way of computer construction. To occupy his time Booth read the Goldstine/Von Neumann papers on the theory of digital computers. He quickly realised that there was no way he could contemplate building an electronic computer in the UK. Resources were in too short supply for a thousand-valve machine. He did find that fast 1ms relays were available and with some clever design, notably a forward carry circuit, he could build an adder that would add two n-bit numbers in around 1ms. The redesigned machine, the ARC2, took advantage of "von Neumann achitechture. It was a parallel stored-program computer and this made it fast even if it was electro-mechanical.

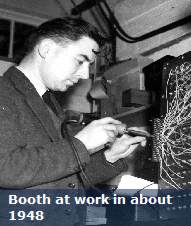

Booth's Magnetic Drum StorageThe real problem Booth had to solve was storage. He worked his way through the possibilities and ended up thinking that magnet storage was the only really practical system. He tried a matrix memory not that far from Forester's core memory, but he couldn't make it work. Then he discovered the "Brush Mail-a-Voice" recorder. This used a 10-inch paper magnetic disk to send a low quality recording of a voice through the mail. Booth took the disk and spun it at 3,000 rpm. The idea was that spinning at that speed it would be rigid and this would allow him to float a head over the surface using the Bernoulli effect. Yes this was the first floppy disk, or was it the first hard disk, or perhaps the first Bernoulli drive! In any case it doesn't matter much because it didn't work. The disk was unstable and it "flapped" so much that the head couldn't get anywhere near it and eventually it disintegrated. As Booth commented: "I suppose I really invented the floppy disc, it was a real flop!". After the floppy failure he turned his attention to a drum. A 2-inch diameter brass cylinder was plated with Nickel and spun. An array of 22 heads read and wrote 21 tracks of data and a single clock track. The whole device gave 256 words of 20 bits and acted as the memory for the ARC which was completed and working in 1948. After further development, the ARC had an electromagnetic store for 50 numbers and a pluggable sequence controller that could hold a program of 300 instructions.

<ASIN:1906124906> |

||||

| Last Updated ( Monday, 31 October 2022 ) |