| The Trick Of The Mind - The Goto Fixed! |

| Written by Mike James | |||||

| Wednesday, 24 December 2025 | |||||

Page 3 of 4

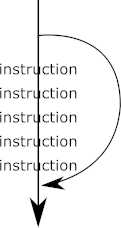

The Goto Can Be Tamed!You might think that it is obvious that any list of instructions built using the Goto can be replaced using these Goto-less control instructions, but to many programmers used to the freedom of the Goto this seemed very unlikely. Eventually a mathematical proof was produced that showed that anything that could be written using the Goto could be written using just If..Then and While. We don’t need to go into the details of the proof, but it is easy to see why it is true and doing so should help you understand the situation better. If you have a list of instructions then a Goto has only two possible ways of affecting the flow of control. Each Goto you find either jumps back in the program or jumps forward. A jump back returns you to an earlier part of the program and so it repeats, i.e. you have a loop and any loop can be implemented using a While. A jump forward skips a section of the program and hence you have a conditional that can be implemented using If..Then. There are lots of technical details to make this a rigorous proof but this is the general idea and it is fairly obvious once you bother to analyze it. Of course, may programmers didn’t bother to do so, they just got on with creating programs still relying on the use of Goto. It is also worth noticing that the If..Then and the While can be implemented using Goto. It would be a huge shock if they couldn’t as the Goto can also implement any program. The equivalent of: If condition Then instruction1 using Goto is: If not condition Goto x instruction1 x instruction2

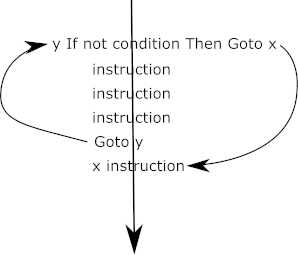

This looks simple, but you have to remember that the condition is to skip the instructions not carry them out. If you think that this is a contorted way of thinking about a conditional you would be correct and it is part of the reason why the Goto isn’t a good way to work. While loops also twist when implemented using Goto: While condition instruction can be implemented using a Goto as y if not condition Goto x instruction Goto y x instruction

This too is an unnatural way to think of things and it is another example of why Goto distorts the way you think of the program. This said, it is clear that you can create programs using the If..Then and While control behaviors just using Goto and your programs would be easier to understand because it avoids using Goto in a wild and uncontrolled way. This would effectively tame the Goto and make some of Dijkstra’s criticisms null and void. Of course, very few programmers worked in this way and it was easier to simply move to a language that banned the Goto and provided instructions like If..Then and While. How One May ThinkAfter this explanation of how the If and While translate to Goto forms you can see that Goto makes the programmer think in a very different way. A Goto can jump back and repeat some instructions or it can jump forward and skip some instructions and this, at its best, is how a Goto programmer thinks. They don’t think of repeating instructions while a condition is true and they don’t think about only carrying out instructions if a condition is true. For example, how does a Goto programmer think about the opposite of skipping an instruction when a condition is true? That is, obeying an instruction only when a condition is true. The solution given earlier is to simply switch the condition to not the condition, but programmers are generally bad at negating a condition. For example, what is the negation of “the value is less than 10 and more than 5”, usually written 5<value and value<10? The answer is “the value is smaller than or equal to 5 or greater than or equal to 10” usually written 5>=value or value>=10. Notice that not only have the greater than and less than signs changed, but the and has become an or. Negating statements is difficult and so many programmers would naturally write something that makes use of the original condition: If 5<value and value<10 Goto 10 Goto 20 10 instruction1 20 instruction2 If your reaction to this is “what?” you are not alone. If you read it assuming the condition is true and then assuming it is false it should make sense. If the condition is true then we Goto 10 and perform instruction1 followed by instruction2. If the condition is false we don’t Goto 10 but we do Goto 20 and so we obey instruction2. You can see that we always obey instruction2 and whatever follows it, but we only obey instruction1 if the condition is true. Twisted? Yes, but it was, and is, the way any Goto-using programmer has to think. This is the sense in which Dijkstra claimed that Goto-using programmers were “mentally mutilated beyond hope of regeneration”. It may seem harsh, but given the way Goto forces programmers to think, it has some justification. You might be wondering why we need to go over this old battle, given it seems to have been won? The answer is that it illustrates the power of algorithmic thought. If you use poor algorithmic thought patterns it makes things more difficult than they can be, but at least you are making progress. With the right set of tools, however, the problems seem easier and the results are easier to understand. The Goto-using programmer sees a mess of jumps where the structured programmer sees conditional execution and loops. The structured programming forms are better atoms to build a thinking universe than the universal Goto. Structured programming leads to structured thinking.

|

|||||

| Last Updated ( Wednesday, 24 December 2025 ) |