| Object-Oriented - Worst Idea Ever? |

| Written by Mike James | |||

| Wednesday, 28 January 2026 | |||

|

or not? There is no denying that the change to object-oriented programming was one of the biggest shifts since we started to use high-level languages - but was it a good move? Given how pervasive the methodology is, the answer has to be "Yes". We all know what objects and object-oriented programming is all about, but exactly why it is so commonplace is a bit more difficult to say. Some of us simply put up with what we are given, but it is important to think about what exactly object-orientation gives us and it is worth remembering that some very clever people have expressed the idea that OOP might not be all it is promised to be. My favourite is by, of course, Edsger Dijkstra, who if nothing else gave us some of the best computer quotes: Object-oriented programming is an exceptionally bad idea which could only have originated in California. I don't know what he had against California, but I think I can understand his dislike of objects. In Dijkstra's day the focus was on algorithms. How could you write chunks of code that did something in a way that was clear? Adding objects to the mix simply took away from the poetry of the code and focused on a larger structure that seemed to have little to do with algorithms. If you don't understand what I am getting at consider the subject of sorting. This is about code that sorts elements into order in the most efficient way - it has nothing to do with objects, even in this object-oriented world. So why are objects so attractive? Back in the day I first encountered practical objects by programming a simple chart object in Simula. I was immediately impressed because after I had created the class I could create as many charts as I needed - hundreds. OK, perhaps I was ignoring the critics pointing out that I had no use for one chart let alone hundreds. It didn't matter much because I was hooked on the power.

What is a object but a function plus some data and I'd have functions and procedures for ages and never was quite as excited by this new idea. On the surface, it seems that the difference is something to do with: chart(data) where the first is a function which creates a chart of the data supplied as a parameter and the second is an object with a chart method. However, the difference isn't just syntactic. The most important difference is that the object persists. That is, an object isn't just a function with data it is a function with state. This is obvious when you are using an object, but not so obvious when you are trying to analyse what is going on. The point is that having a chart object makes you think that the object exists in some sense for the duration of the program - or for some other well defined lifetime. The function, on the other hand, only exists when it is executing. It is a transient phenomenon. It comes and goes as you call it, but a chart object with a draw method persists. So much so, that it becomes obvious that it should have methods that modify its current state: chart.draw() Now we have a method which changes the background color of an existing chart object. Notice that this is natural to adopt, use, understand etc. Compare this to the idea that you might modify the background color of a chart drawn by a chart function? It's possible, but the idea that the function does its business and then vanishes means it is difficult to connect to any state it has constructed and then left behind. It is the persistence of objects that makes the idea that they hold mutable state so attractive. For the moment, we can ignore the functional programming idea that mutable state is a bad idea - simply because in object-oriented programming it is unavoidable and a good idea. Getting rid of mutable state is difficult without using nothing but recursion and that isn't so obviously a good idea either. So objects persist and provide a way to represent and work with a mutable state. What about the other supposed advantages of objects - encapsulation, inheritance and polymorphism. Well to be honest they don't actually affect the average programmer that much. Why not? Simply because the average programmer is an object-consumer, not an object-constructor. That is, when you sit down and start a program you basically instantiate the objects you need and start using their methods. You do not start off building deep hierarchical class libraries. Any classes you do create are very simple and tend not to inherit from anything complex. This is possibly one of the reasons Python is so successful. Python is full of preconstructed objects ready to do your bidding. It is why so many Python programmers aren't 100% sure about how to create new classes. They don't need to dig that deep to get useful things done.

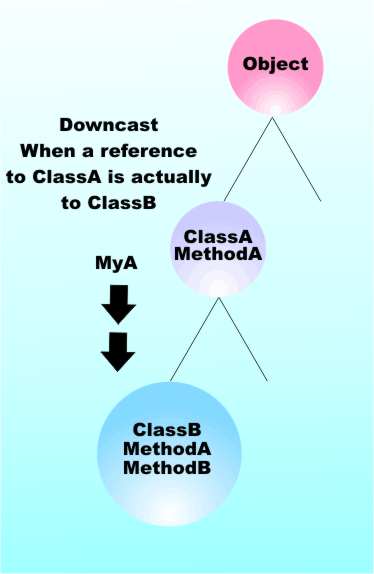

It is only the designers of class libraries who need to believe in the effectiveness of inheritance and polymorphism. The rest of us can take advantage of encapsulation and the persistence of objects. As a way of delivering libraries of code objects are great, but mostly we don't need to go any further than using the objects that others provide. It is the others who must struggle with the complexities that drinking the object koolaid brings on - inheritance, polymorphism, type hierarchies, liskov's principle, variance, generics and so on... If objects are such a good idea when you are working with algorithms, why is the most promising language of the present, Rust, not object-oriented? When you get down to writing algorithms objects are irrelevant. Related ArticlesThe Trick Of The Mind - The Benefit Of Objects What Exactly Is A First Class Function - And Why You Should Care Towards Objects and Functions - Computer Languages In The 1980s To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter, subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Facebook or Linkedin.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info |

|||

| Last Updated ( Wednesday, 28 January 2026 ) |