| Linux Demonstrates That Bugs Can Hide For 20 years! |

| Written by Mike James | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wednesday, 14 January 2026 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

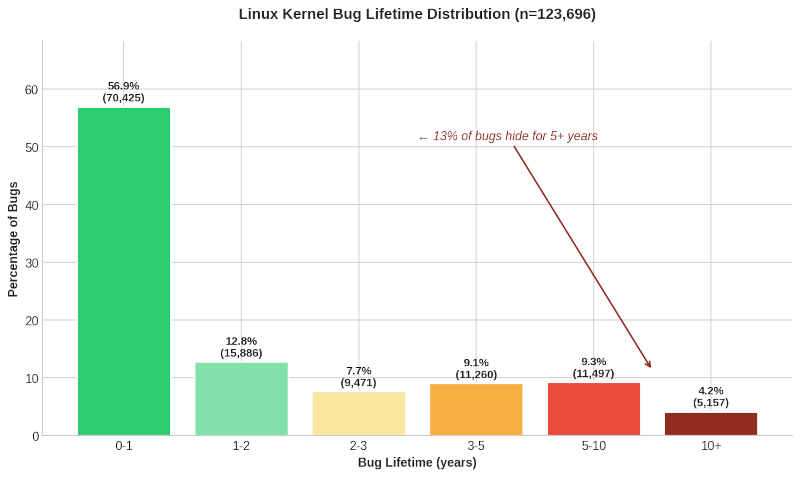

A very nice analysis of Linux commits reveals some interesting things about bugs - and how long they take to fix isn't the most interesting. Jenny Guanni Qu, a researcher at Pebblebed, has written some code to find out how long it takes to find a Linux bug with some very interesting conclusions. If you want the details and many observations then read her blog post with the title "Kernel bugs hide for 2 years on average. Some hide for 20". This is data mining at its best. I just want to say a few things that occurred to me as interesting. The headline-grabbing "20 years to find and fix a bug" isn't as shocking as it sounds - it was a buffer overflow in ethtool. Generally this is only used by specialists who probably could live with the problem. Even so, 20 years is a bit of a go-slow. The non-outliers were also reasonably understandable. Bugs in drivers took 4.2 years to find, which is probably a reflection of how specialized driver development is and how easy it is to ascribe weird behavior to the hardware. In fact, most of the longer lived bugs were in minority-hardware areas. The big exception being the ext4 file system which on average took 3.56 years to find. Which, given it is the default for many distributions, makes you think that there is some less obvious reason.

As interesting as the actual time taken is, it seems that we are getting better at finding bugs. In 2010 a bug had an average lifetime of 9.9 years, but this falls to 0.8 years in 2022. This could be because the later bugs just haven't had time to be detected as yet. But even allowing for this artifact the time to find does seem to be going down. Now we come to the part that I found most interesting - bug by type:

If you had asked, I would have guessed either deadlock or race condition would top of the list arranged in terms of time to correct. This is simply because both are far too easy to put down to hardware problems. The rest, less so. I'm particularly surprised by integer-overflow being second in the list. Is it a lack of error messages that lets this most obvious of errors go unnoticed? You can't put an integer-overflow down to something hardware-related unless you try very hard. I suppose it could be that they are so easy to detect that so few buffer-overflow errors make it into production code and presumably they hide in virtually untrodden paths. This idea of investigating how bugs go unnoticed deserves more attention. Jenny Guanni Qu clearly thinks so as well and she investigated using AI to predict if a commit was likely to introduce a bug. Her creation VulnBert manages a 95% correct guess at which commits did eventually prove to have introduced a bug and with only a 1.2% false positive rate. That sounds worth trying out. I guess it might make the bugs even more visible. More InformationKernel bugs hide for 2 years on average. Some hide for 20. Related ArticlesThe Trick Of The Mind - Debugging As The Scientific Method AI Finds Vulnerabilities - Not Everyone Is Happy Automatic Testing - Programmers Are Still The Problem Code Digger Finds The Values That Break Your Code To be informed about new articles on I Programmer, sign up for our weekly newsletter, subscribe to the RSS feed and follow us on Facebook or Linkedin.

Comments

or email your comment to: comments@i-programmer.info |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last Updated ( Wednesday, 14 January 2026 ) |